Elizabeth Price talks psychedelic carpets and library utopias in her new show at The Hunterian

Artist Elizabeth Price creates powerful works that examine artefacts and objects which are often considered insignificant. In attending to overlooked processes and details, her works unwind complex social histories shaped by class and gender. She was awarded the Turner Prize in 2012 for her video The Woolworths Choir of 1979.

Elizabeth’s new exhibition UNDERFOOT, at The Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, is her first solo presentation in Scotland. It follows research undertaken at the Stoddard Templeton Design Archive during a fellowship with the University of Glasgow Library. James Templeton & Co Ltd was once Glasgow’s largest employer, with around 7,000 employees in the 1950s. The company exported globally and was commissioned to make carpets for parliaments, coronations, concert halls and public institutions.

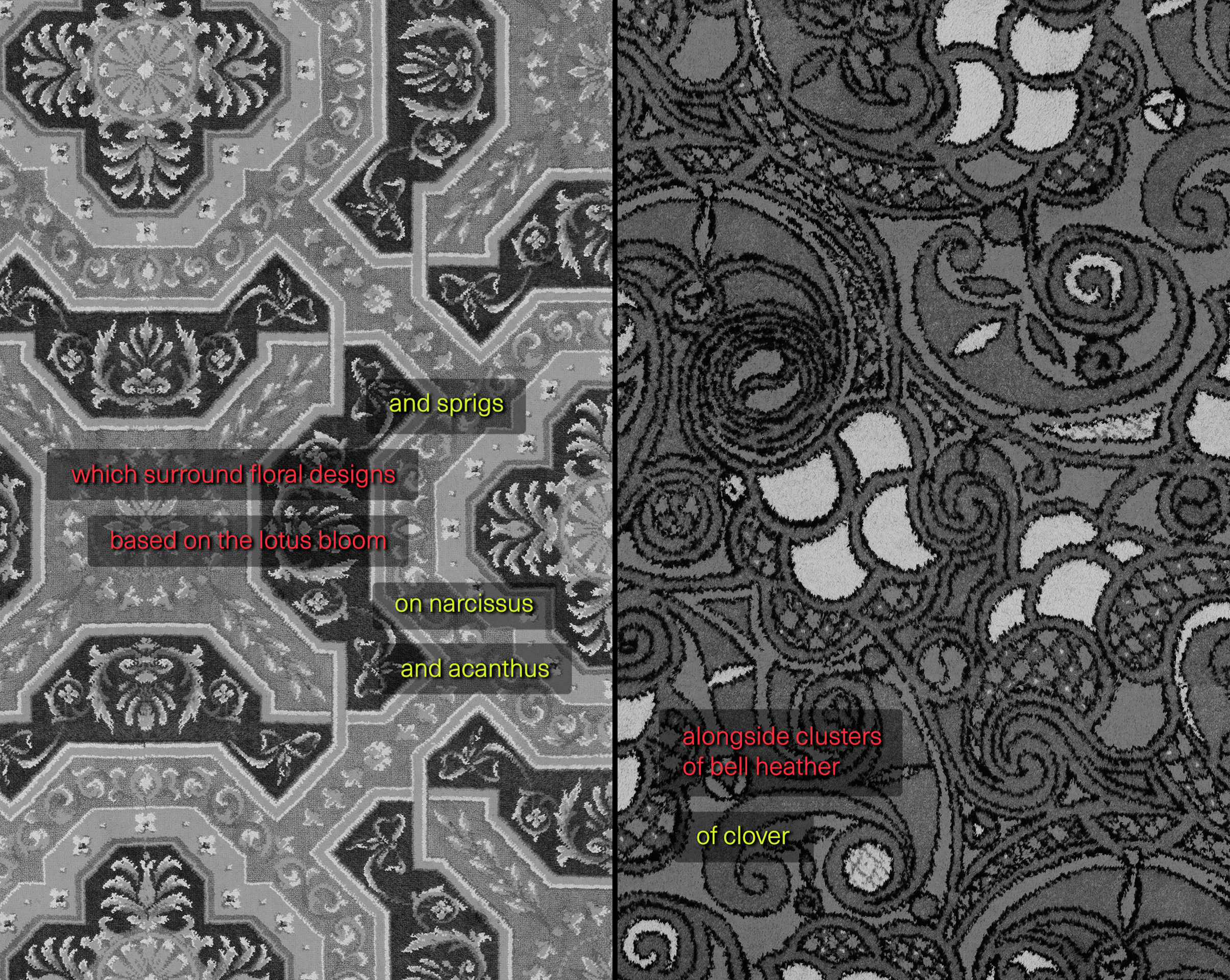

The exhibition unpicks the twinned industrial and imaginative histories of textile design in the city, through the renowned carpets of Glasgow’s Mitchell Library, where repeat geometry, foliate patterns and kaleidoscopic motifs offer a map for the wandering mind. A celebration of civic architecture, UNDERFOOT calls attention to the power of public provision in creative exploration.

Marcus Jack, Programme Lead, sat down with Elizabeth to talk through the project.

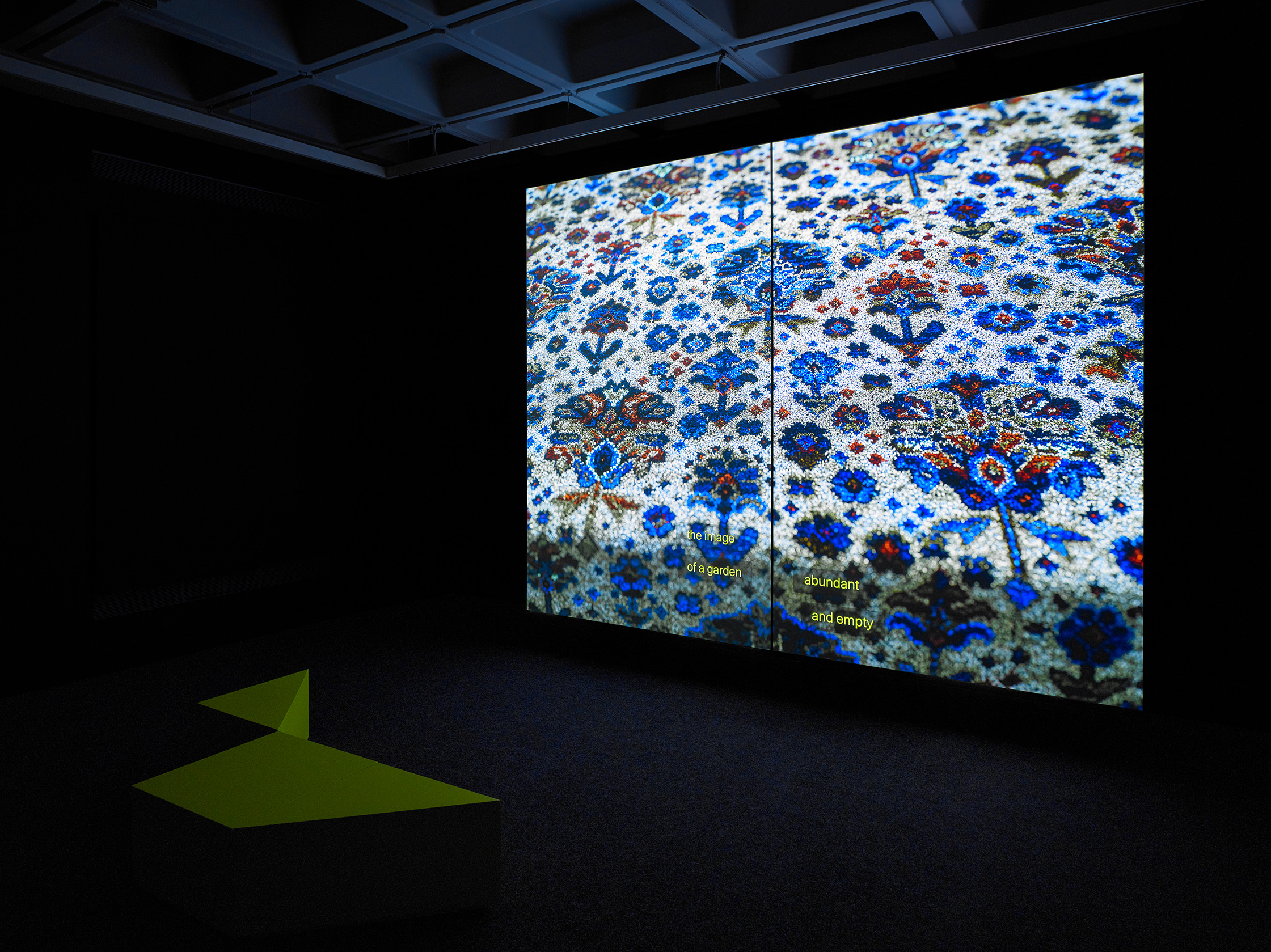

Elizabeth Price, SAD CARREL, 2022. Installation view. Photo: Andrew Lee.

Marcus Jack: I was wondering if you could just tell me a bit about the making of the work?

Elizabeth Price: I was invited by Fiona Jardine of The Glasgow School of Art to consider the possibility of making a carpet, which as someone who normally works in moving image might seem strange. It was really intriguing, partly because a number of films I’ve made have focused on the shared history of digital technologies and textiles. The Hunterian got involved and I had access to all of the University of Glasgow’s archives and particularly the Stoddard-Templeton Collection. I spent days working with those archives alongside Dr Jonathan Cleaver, who is a former Master Weaver and expert on Scottish carpets. I really immersed myself in that material. That’s really part of my process: I like to totally bury myself in material in the archive so that I feel surrounded by it.

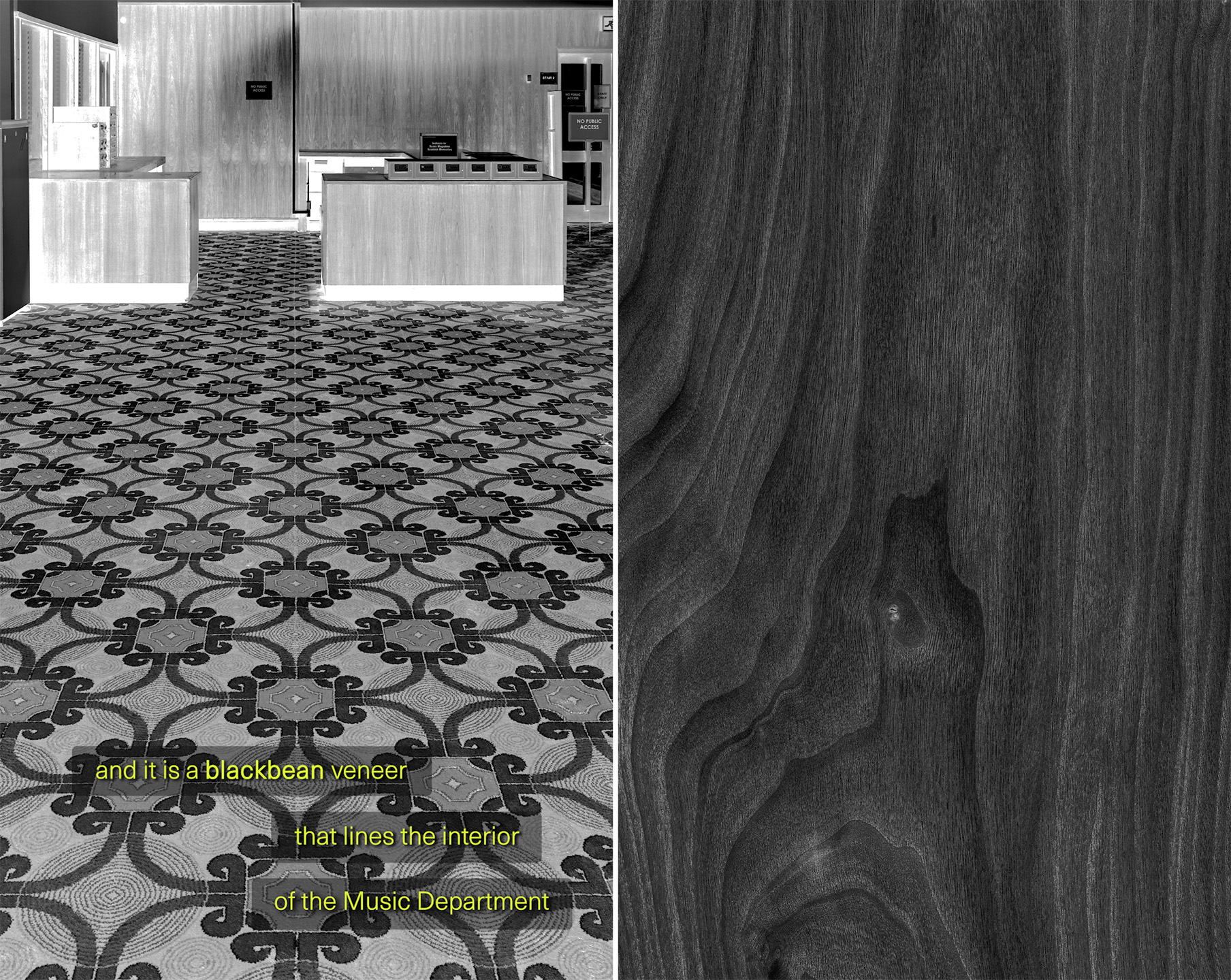

One of the key moments of the whole project was when we’d spent a day in the archives, looking at these repeat patterns and Jonathan suggested we actually see what they look like. We went to the Mitchell Library and I just thought it was amazing: the combination of that late modernist architecture and those carpets, the really unusual optical intensity of the decor, through those carpets. It’s unusual for a library, almost like there’s a desire to distract you, to let you mind take a journey. The combination of the library and those carpets proposes something about how knowledge works or what was possible to think about. It might be much more about imagination than this late capitalist knowledge house, growth and productivity. Encountering knowledge can be sensory, exciting and psychedelic and that’s what those carpets remind me of.

Elizabeth Price, UNDERFOOT, 2022. Installation view. Photo: Andrew Lee.

It’s such a fitting installation with the cast concrete ceiling here in the exhibition space. I was also interested in thinking about carpet-making as a form of computing, or the Jacquard loom as an early computer, and I wonder if there’s anything material about the subject that you were looking at that has infiltrated the way that you made the film?

I was very interested in that shared history, particularly in the Jacquard loom. During this project, I became fascinated by this different kind of loom, the Spool Axminster loom, in which each line of the design is separately wound onto reels as part of the process. The spool loom literally resembles the film loops you see in a gallery presentation but also how video was built up through a series of stacked lines, in terms of earlier interlaced video images. A less straightforward relationship than perhaps the Jacquard loom but an awful lot of the same things apply: this inputting of data, line by line.

My video installations are always immersive and very definitely a black box, a space like the discotheque, like the nightclub and the theatre. That sense of being in a world is one of the things I always try and achieve with the acoustic creation of the work, the projection and the environment we’ve built. So, apart from the technological associations with video, the thing about carpet which interested me was the idea that it creates a social and imaginative space into which you enter. One of the discrete but incredibly powerful things about carpet is the way it impacts the sound of the space and how you feel it under your feet. You’re barely conscious of these things but in a minute way they effect how you think.

Because they are this horizontal space, so much of carpet design depicts a kind of terrain: the preponderance of foliage and flora, the traditional idea of the carpet as a garden. I was really fascinated by the idea that the carpet figures an ideal space, even in images that are relatively abstract.

They are such places of fantasy. I remember when I was kid and we had a big Persian rug in the hall and I would pace it round and round, see shapes in it.

Absolutely, I remember playing on carpets where the different areas would become a mountain or a road that you drive cars around.

Still from Elizabeth Price, UNDERFOOT, 2022. 2-channel video projection. Courtesy of Elizabeth Price Studio.

I was wondering about the significance of Glasgow in this work and whether you found any narratives there that you’d like to share?

I definitely felt affection for Glasgow, and I think that’s possibly in the work. It’s really all about Glasgow and I think people who know the Mitchell Library will identify that. It never mentions the city, however, so in a sense I want people who are not familiar with those histories to still be able to encounter it through the principle of a library.

I came to Glasgow a lot on when I was young and in bands. The first art world I was involved in was the music world, post-punk and indie. That’s one of the things that has been really key for me, the sense of growing up within a sonic world. That’s not unique to Glasgow and lots of cities have it, it’s very strong in the UK. You go to any coastal town and there’s a guitar shop, I’ve always noticed that. People are maybe not that fond of contemporary art in the UK but you can go to any town and see a band there. It’s a really distinctive and affirmative thing about our national culture in the UK: the love of music. I think part of what was important to me was the environment of the carpets, of the libraries and different public spaces that surround Glasgow’s culture of music-making.

Still from Elizabeth Price, UNDERFOOT, 2022. 2-channel video projection. Courtesy of Elizabeth Price Studio.

There’s something so important about these Keynesian hangovers and little utopias from the 1960s and 1970s.

Yes, all this creativity flourished because of that and I think that’s what fascinated me about the Mitchell. It wasn’t only the carpets but the inclusion of these sound-enclosed spaces called carrels. There was this space in the library for the making of noise, for the making of music. Although they’ve not survived there were also areas for the making of art—splash areas with sinks. You can still see the sinks in the library. Some of the early photography of the Mitchell shows people working on easels. There was this idea that art and music were absolutely part of cultural heritage and that the library was this resource for people to be creative, for imagination and invention. I’m certain that if you make that provision possible it does something.

Well long may they live, I hope. Lastly, what does it mean to have this show in The Hunterian specifically?

I think this building is remarkable. Small but beautifully designed spaces with this unique entrance, the circular staircase. There are all these correspondences between the architecture featured in the film and the architecture of the show. Of course, the access to all the historical materials in the university archives has also been great but I have to say that the most amazing thing has been working with the people at The Hunterian, Panel, The Glasgow School of Art and Dovecot Studios. It makes a real difference to how confident you feel, everyone has been incredibly generous.

UNDERFOOT continues at The Hunterian Art Gallery until 16 April 2023.